Here’s a fascinating list of Scottish words we use. (At least, I do.) And a completely separate list of Gaelic words. Gin ye daur, hae a keek. Dinna be blate – or aabody will jalouse ye’re a gype. (Hey, how am I doing here? Of course Scots is a language, not just an accent.)

How Do The Scots Speak?

So, if you’ve read the Scottish accent page – and you know you should – you will have jaloused (worked out) that everyone in Scotland speaks English, but the Lowland Scots language varies.

At its ‘mildest’, it’s basically English with a certain accent and perhaps the odd Scots word. On the other hand, you can also hear ‘dense’ forms of Scots with a lot of unfamiliar Scottish words and different pronunciation.

Here’s a kind of representative sample of Scottish words.

Even some of the words given here would be unfamiliar to, say, someone from the Central Belt of Scotland, especially if they came from a middle-class aspirational background or had gone, say, to a posh Edinburgh school.

But, hey, personally, I’d certainly use these Scottish words when talking to northern friends or family, and occasionally perhaps just to annoy other Scots – or even my own children – who may be in danger of losing their linguistic heritage. Only joking about that. (I think.)

Scots borrows widely from other European languages. I sometimes say ‘Dinna fash yersel’ – don’t worry or put yourself to bother – from the French se fâcher: to get angry, annoyed.

Or if I am hot I might say I was ‘fair plottin’ from middle Dutch ploten: meaning – wait for it – to remove wool or skin by immersion in boiling water.

I might keek instead of look – also prob. Dutch: kjiken.

Or I might buy something at a roup – originally from Old Norse raupa – to shout out.

The other element of Scots (ie the Scots language) is that sometimes it sounds ‘different’ even when using ‘standard English’ words in characteristically Scottish constructions.

For example ‘doing (or going) the messages’ is getting the shopping or ‘I’ll see you the length of the bus stop’ – I’ll go with you as far as the bus stop. The usage of ‘English’ is Scottish, yet contains no Scottish words.

And there are many Scottish idiomatic phrases, such as the splendid usage for something that goes ‘pear-shaped’ . In many parts of Scotland it’s ‘tatties ower the side’.

For ‘Tatties ower the side’ explanation below, follow link.

Scots therefore is not just a matter of a different accent and a unfamiliar vocabulary of Scottish words. Sometimes the way we put together the sentence can vary from ‘standard English’.

OK, here goes with a list of some Scottish words (starting below the picture of the Waterstones bookshop window in Aberdeen) – but can you trust a loon (boy) from the depths of North-East Scotland to come up with a wee Scots glossary?

Some Scottish Words

For some Gaelic words – as opposed to Scots words, see further down the page…..

Scots, (bolded) with English definitions:

chap (v or n) knock or beat (as in chappit tatties – mashed potatoes) Note this isn’t the same as chap, informally meaning a man in English. For that I would say chiel.

dachle (v) hesitate, dawdle or ‘take your time’ (cf swither, below).

douce (adj) sweet or pleasant. Sometimes also respectable.

gey (adj) very. So the dance The Gay Gordons is really the Gey Gordons – meaning the pretty damned impressive and scary Gordons.

dreich (adj) dull. Of weather – or tourism conference speakers.

graip (n) garden fork (eg for lifting tatties – potatoes). You’ve never heard this? My dad never called a garden fork anything else.

loup (v or n) jump. So, loup the cuddy – leap the donkey – is really leapfrog.

orra (adj) (either) dirty or spare. You still see adverts in the farming press for an orraman – a handyman. An orra-tongue would be foul-mouthed but an orra-loon could just be a spare boy on the farm.

scunner (n or v) nuisance or irritation. I was so scunnered trying to line up this set of words that I almost gave up. But you’re worth it.

shoogly (adj) unsteady. ‘My job’s on a shoogly peg.’ – ‘I have an uncertain future at work.’

skelp (v or n) slap, as in a skelp on the lug (or the erse) – a slap on the ear (or the behind).

skite (v) slip ‘Haud ma airm. Affa skitey flairs.’ – ‘Hold my arm. Very slippery floors’. (I overheard this in a shopping mall in Elgin recently!)

stravaig (v) wander or sometimes go off on a ploy. Oddly enough there’s a moment in the movie Mary Poppins, (the Julie Andrews one) when the children are told to ‘stop stravaiging about’. While we would pronounce stra-vaig-in, there the nanny says stra-vidging.

swack (adj) supple, fit. Not to be confused with…

swick (n & v) to cheat, swindle.

sweirt (adj) unwilling, reluctant. ‘Swiert tae pert wi siller.’ Unwilling to part with silver, ie money.

swither (v) to be uncertain or hesitant, especially between two options. I was swithering about this word list – make it long or short? I’ve gone for quite short, but, wait, there’s more below. Dachle a while…..

yirdit (adj) covered in earth, mucky or just bogged down. It’s also what I’ve called my Scottish gardening website.

Scottish words: Gaelic Place Names And Landscape Features

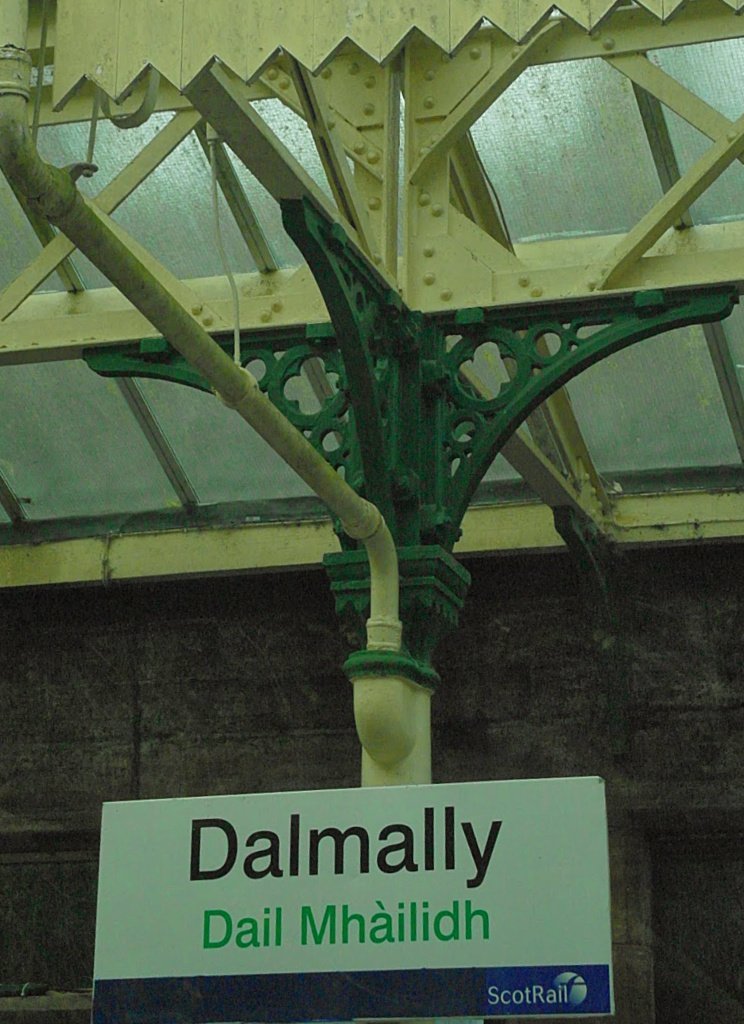

The traveller in the Highlands (and in other parts of Scotland) will frequently encounter Gaelic place names, some specific, others turning up as, for example, prefixes or parts of many place names.

Here are some examples of Gaelic words which occur (often as part of road signs) in many parts of Scotland – though mostly in the Highlands, naturally, as the homeland of the Gaelic language – the oldest of Scottish words.

Full disclosure: I have to let you know that I am a native Scots speaker, not a native Gaelic speaker – my knowledge of the language mainly confined to place-name elements. But here goes anyway…

Gaelic place name elements, with English translation

aber, (and) inver both mean river mouth or confluence, the ‘inver’ prefix being the commoner. Inverness – the mouth of the Rive Ness, is the best-known.

achadh field. Common Gaelic prefix – Achnasheen – the fairy field or Achnashellach – the field of the willows.

ard, aird high point – Ardnamurchan – the point of storms.

allt burn (in Scots), stream or river (in English)

beag small, so Ardbeg is the small high point

bealach pass – most famously in Wester Ross’s Bealach na Ba – the pass of the cattle.

caol, caolasa (sea) straight or inlet, usually ‘Anglicised’ to Kyle and common on western seaboard maps.

coille wood

drochaid bridge

drum, druim ridge – so Drumnadrochit on Loch Ness is a ridge by a bridge. (Isn’t it?)

garbh rough. Garve is also a small community west of Inverness.

gorm blue or bluey-grey (cf Cairngorms ‘blue stones’)

kin, ken (ceann) head – so many Kin suffixes, such as Kinlochleven – head of Loch Leven, Kinlochard – etc. Also Kinnaird, my son’s name. I translate this loosely as ‘head of a high place’ or ‘chief executive’ but so far, no luck.

meall round hill. As a place name prefix often anglicised to ‘Mel-‘

ros, ross promontory or moorland

tigh house. Tighnabruach – the house by the bank.

uig bay. Also specific place name on Skye.

uisge water. I like ‘each-uisge’ – water horse – spooky Gaelic name for Loch Ness Monster or kelpie. Ho-hum. It’s likely that river names: Esk, Usk, Ugie etc are related to this.

More Scottish Place Name Elements

In case you think this is all north of Scotland stuff, if you take a look at any Ordnance Survey map of the South of Scotland you’l find lots more place names and landscape features – typically Scottish words.

cauld – a weir or dam.

cleuch – a gorge, ravine or (sometimes) a cliff.

fauld – a fold or small enclosed piece of ground for cultivation.

hope – a small enclosed valley or hollow among the hills.

heugh – crag, cliff, or steep bank above a river.

howe – as above, a hollow.

kip – a jutting point on a hill, or the peak itself.

knowe – a knoll, small hill.

rig – ridge or high ground or narrow hill, or narrow strip of land.

shiel – a hut or small house, (or summer pasture with a shepherd’s hut).

shaw – a small wood or thicket.

steel – a steep bank or spur of a hill ridge.

syke – a marshy hollow, often with stream (or do I mean ‘burn’?)

More on how we speak on the Scottish accent page.

Tatties ower the side!

As promised, here’s the explanation for this colourful Scottish phrase. It’s slightly non-PC but bear with me.

By way of background, my wife has an English father, hence her linguistic heritage of Scots vocabulary was formerly limited.

There’s nothing wrong with that – especially since her Scottish mother had some Gaelic words by way of compensation. In addition, my wife was brought up in Edinburgh, a cosmopolitan place that can hardly be described as a repository for our older tongue.

However, as she then lived in North-East Scotland for many years she picked up some fine and colourful expressions.

I overheard her using one on the phone just the other day. Basically, if a certain chain of events took place I heard her say, ‘then it’s tatties ower the side’.

I think it was something to do with some spoon-fed media representative or blogger on a trip underwritten by the tourist board. It seems if (s)he wasn’t driven to the airport by such-and-such a time, (s)he would miss his plane. Yup, tatties ower the side all right…

I could also tell that the person she was speaking to, who was also a Scottish travel guide, had never heard the expression before. So in the interests of preserving something colourful, she went on and explained it to him.

It’s a very useful expression, by the way, and means, obviously, that if a certain thing happens, then the plan falls apart. I suppose it might be the equivalent of something ‘going pear-shaped’.

(And if someone could explain that phrase, I’d be most interested.) The ‘ower’ (or o’er) is, of course, ‘over’ but pronounced to rhyme with ‘hour’.

In the days of the herring drifters

I think it may be a reference to an old and slightly non-PC story about a cook aboard a steam fishing drifter – yes, that old – who was making a meal for the crew. This was almost sure to have been tatties and herrin. (Potatoes and herring.)

It was a rough sea (or what the crew would have called ‘a coorse day’). When the tatties were ready, the cook had to drain them.

He came out of the galley, leaned over as the boat gave a lurch and drained away not just the boiling water but also the contents of the pot.

He was distraught and rushed to tell the skipper in the wheelhouse about the culinary disaster. Unfortunately, this cook also had a speech impediment, a stammer (which is why it’s a non-PC story).

He opened the wheelhouse door and tried to communicate, again and again, but barely got past the initial syllable.

The skipper was attending to the hauling of the nets, and watching the weather and the course, and growing more and more exasperated at the figure beside him, opening and shutting his mouth.

Finally, he turned to his cook and said ‘Oh, for god’s sake, Jimmy, will ye just sing it’. Whereupon, in a fine baritone voice, with perfect enunciation, Jimmy the Cook sang out (of course) ‘The tatt-ies is ow-er the si-ide’.

(I think it works best in 3/4 or waltz time.)

That’s it – literally the potatoes had gone over the side of the boat.

All right, I agree, you have to be able to time it right and really sing out yourself if you’re telling this story – but it still gets a laugh, even to this day. Come to think of it, that perhaps says something about the company I keep.

More to the point, it also shines a light on the droll Scots’ sense of humour. So, next time you believe something’s about to go pear shaped, forget the fruit and go for the veg. It’s ‘tatties ower the side’.

More on how we speak on the Scottish accent page.

If you’ve read this far, then you’d probably enjoy Billy Kay’s The Mither Tongue.