Robert Louis Stevenson followed a literary calling. Though abroad for much of his life, Stevenson’s love for Scotland shines through in his writing.

It can’t have been easy being the young Robert Louis Stevenson.

Born in 1850 into a very respectable, well off and prominent Edinburgh family already noted for pioneering engineering work in connection with lighthouses and harbours, he did not follow the career expected of him and hence disappointed his parents.

First, he had played truant instead of studying maths and sciences at Edinburgh Academy. At age 18, instead of being Robert Lewis Balfour Stevenson, he asked to be called Louis.

Then he adopted an unconventional, almost Bohemian way of life at university.

Imagine how that would have gone down with his serious, purposeful, practical father, Thomas, the designer of many major lighthouse projects such as Out Skerries, the Butt of Lewis and the lonely Dhu Heartach.

Stevenson Father And Son – A Battle Of Wills

In the ensuing battle of wills, his father Thomas was determined that Louis should pursue a career as an engineer (and thus toe the family line).

He took the young Stevenson on works inspection tours – in 1868, to Anstruther in Fife, and Wick in Caithness. (Read the description of Stevenson’s descent in a diving suit there in his Picturesque Notes.)

But Robert Louis Stevenson spent his time chatting to the old fishermen, rather than noting down engineering details.

In 1870, he was taken on a lighthouse tour, where, again, in the later Memories and Portraits, it is character and scenery rather than technology that he describes.

He would later put his landscape knowledge to good use as a dramatic setting for various works, notably Kidnapped. (See The Appin Murder, below.)

By 1871, he had shocked his father by announcing that he would definitely not be an engineer. They compromised and he was sent to study law – which Thomas saw as a safety net should his son’s chosen path of becoming a writer not work out.

But his father, it seemed, remained a little bitter ever after….

Robert Louis Stevenson’s Life As A Writer

Having resolved to become a writer, his early works were written in the family’s house in Heriot Row or at their cottage at Swanston.

By 1877 he was in journalism in London and the centre of a literary and artistic club circle.

On one of his frequent visits to France, he met Fanny Osbourne. He eventually followed her to California and married her in 1880.

His health was meanwhile failing, damaged by the American journey.

He returned to Europe in early 1881 with his wife and stepson. They lived in a series of temporary homes, which included, in Scotland, Pitlochry in Perthshire, where the landlady of his rented cottage had a store of ghostly Highland tales.

One of them inspired the piece Thrawn Janet, written in broad Scots but accepted by London’s Cornhill Magazine and described by the novelist Henry James as ‘a masterpiece in thirteen pages’. (Thrawn is Scots for stubborn.)

The Origins Of Treasure Island

During the summer of 1881 (which was wet and kept Stevenson indoors writing!) the family moved from Pitlochry to Braemar. There perhaps his most famous book, Treasure Island flowed easily but hurriedly from his pen – the first fifteen chapters in as many days.

Subsequently, for health reasons, as his worsening tubercular lung condition was not improved by the Scottish climate, he lived in Switzerland, the south of France and the south of England. He published several books, which brought recognition and financial success.

After returning to Edinburgh on his father’s last illness, he left in 1887 for the South Seas, eventually settling in Samoa. He remained there until his death in 1894, producing some well known works, though never forgetting his native city.

He died aged only forty-four – an age when Sir Walter Scott, for example, was only just beginning to create some of his best material. (Imagine what might have been, had Robert Louis Stevenson lived, say, into the 1920s or 30s.)

Places Associated With Robert Louis Stevenson

The Writers’ Museum, in Lady Stair’s House, near Edinburgh Castle at the top of the Royal Mile, is one of the City of Edinburgh’s own museums and has plenty of Robert Louis Stevenson memorabilia.

(The family’s former home at 17 Heriot Row is NOT a museum. There is an information board on the railings opposite)

Edinburgh Castle features as the prison of the French hero of St Ives who makes a dramatic escape down the Castle Rock.

Swanston, just south of Edinburgh, below the Pentland Hills, is a tiny, picturesque hamlet. The Stevensons leased Swanston Cottage (originally built by the Edinburgh city authorities and quite a large house – also private.)

The Cottage gives its name to a chapter in St Ives where it is described as a ‘rambling infinitesimal cathedral….grotesquely decorated with crockets and gargoyles, ravished from some medieval church.‘

This is a reference to the building material re-used here by the city authorities. The stonework had originally come from St Giles Cathedral after its severe restoration in 1828!

Colinton, a suburb of Edinburgh, also has a selection of walks in the wooded river valley of Colinton Dell, near the home of Rev.

Dr. Lewis Balfour, the maternal grandfather of Robert Louis Stevenson. The Rev. Balfour was once the minister of the Parish Church here. Descriptions of manse and garden (private) can still easily be recognised today.

Robert Louis Stevenson spent many happy days there, often recuperating from the variety of childhood illnesses from which he suffered

Early memories of the nearby mills on the riverside are recalled in his verses ‘Here is the mill with the humming of thunder/Here is the weir with the wonder of foam.’

South Queensferry, near Edinburgh, has magnificent views of the Forth Bridges, and the old Hawes Inn features in Kidnapped. Stevenson as a young man frequently walked out from Edinburgh to South Queensferry.

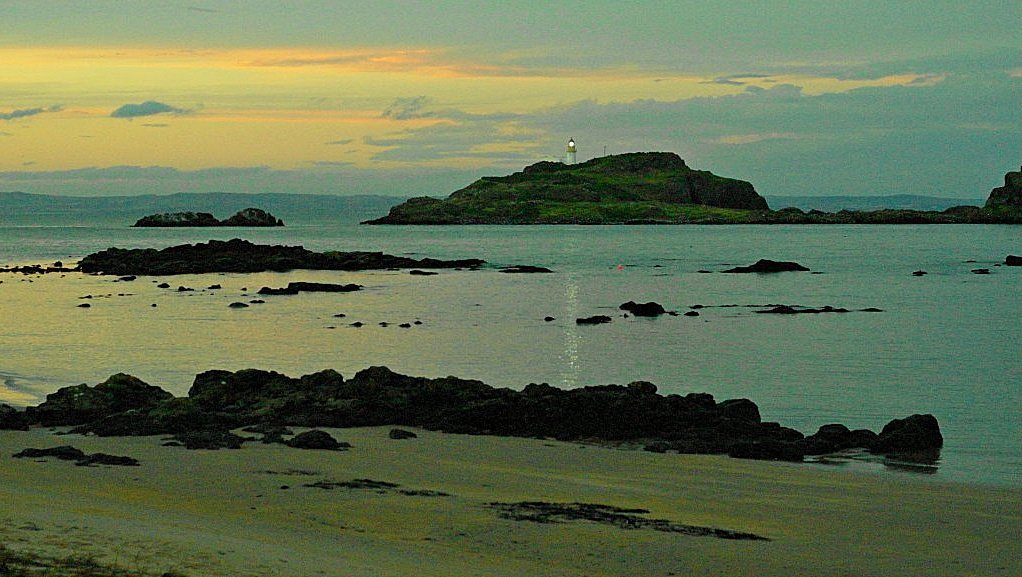

Around the Lothians and Borders, the small island of Fidra (pictured here) in the Firth of Forth near North Berwick is mentioned in Catriona.

There is a good view of Fidra from the shore at Yellowcraigs, reached from Dirleton west of North Berwick. I made a painting of this view and a fine art print of this can be purchased from my Etsy shop.

It is also said to have been a source of inspiration for Treasure Island – as have several other places, including the view from Stevenson’s Heriot Row bedroom window, out to a pond in the nearby gardens!

Catriona also has vivid descriptions of East Lothian coastline including the Bass Rock, (pictured here), where David Balfour was made prisoner.

In Catriona, the chapter called ‘Gillane Sands’ (now Gullane) captures the breezy ambience of the coastline : ‘there was such a shining of the sun and the sea, such a stir of the wind in the bent grass, and such a bustle of down-popping rabbits and up-flying gulls….’

To discover the boisterous air of the East Lothian beaches, follow this link to the East Lothian tour from Edinburgh.

Inland, Robert Louis Stevenson’s knowledge of Lammermuir Hills provides the setting for Weir of Hermiston. Further afield, part of the action in The Master of Ballantrae is set in Borgue in Kirkudbrightshire.

Also, the house in which Stevenson stayed while in Braemar, west of Aberdeen in Deeside, is now called Treasure Island Cottage (private) to recall its role as the place where his masterpiece Treasure Island was conceived.

At Bridge of Allan, near Stirling, on the banks of the Allan Water, is a small cave associated with the author. He spent boyhood holidays in the little town nearby.

Robert Louis Stevenson had the great skill of making landscape come alive, so that it becomes an integral part of the adventure.

Thus in Kidnapped, David Balfour and Alan Breck, pursued by redcoat soldiers, came to Rannoch Moor (below) where:

‘the mist rose and died away, and showed that country lying as waste as the sea; only the moorfowl and the peewees crying upon it…‘

Robert Louis Stevenson And The Appin Murder

In writing Kidnapped, Stevenson wove into the plot an unsolved Highland mystery: the murder of Colin Campbell of Glenure. This real life event took place in 1752, in troubled times after the final Jacobite uprising had been put down at Culloden.

Bitterness between Jacobite clans such as the Stewarts of Appin and their protagonists (and landlords), the Campbells, resulted in the murder of the local laird, Colin Campbell. Stevenson took many liberties with these basic circumstances to ensure a good story.

In Kidnapped, David Balfour’s adventure, which started in the Hawes Inn, can be traced by sea round the coast of Scotland to the point of shipwreck on the Torran Rocks by Earaid Island off the larger island of Mull.

Fugitives on Rannoch Moor

Robert Louis Stevenson had visited the site when the lighthouse of Dhu Heartach was still under construction, with his father and his Uncle David overseeing this project to make the dreaded reefs of the Torran Rocks safer.

In his famous adventure story, the narrative takes the adventurers eastwards through the heart of Scotland: across Mull and Morven, by way of Loch Linnhe and Glencoe to Rannoch Moor and then into the mountain fastness around remote Ben Alder in Perthshire.

Eventually, Balfour and Breck make their way southwards to cross the Forth near the little town of Culross, where the little houses with their 18th century architecture, around the period which Stevenson described, have today been picturesquely restored.

Back in Appin, the Monument to James of the Glen (condemned to death, though innocent of the murder) is seen near the present Ballachulish Bridge. The murder site is marked by a cairn on the wooded slopes of Letir Mhor, west of Ballachulish and reached by a forestry track.

Find out about Robert Burns, another Scottish literary figure.