Culloden Battlefield saw the last battle on Scottish soil. Not Scots v English, but a civil war. Great on-site visitor centre. A Highland must-see. And though it’s a designated war grave, no regiment in the British Army has it listed on its battle honours. Visit and you’ll find out why.

The National Trust for Scotland look after a range of properties in Scotland, from humble homes to grand castles. (They lean towards grand castles.)

They also own wild land and historic sites, of which Culloden Battlefield is probably the best known.

They are a conservation and heritage charity and are supported by members. Basically, right now, times are tough and castles are expensive to maintain. This is another reason why you should include their battlesite visitor centre on any Inverness visit.

For interpretation, for a learning experience, for an insight into how Scotland stood in the mid-18th century, the National Trust for Scotland have really delivered quality here.

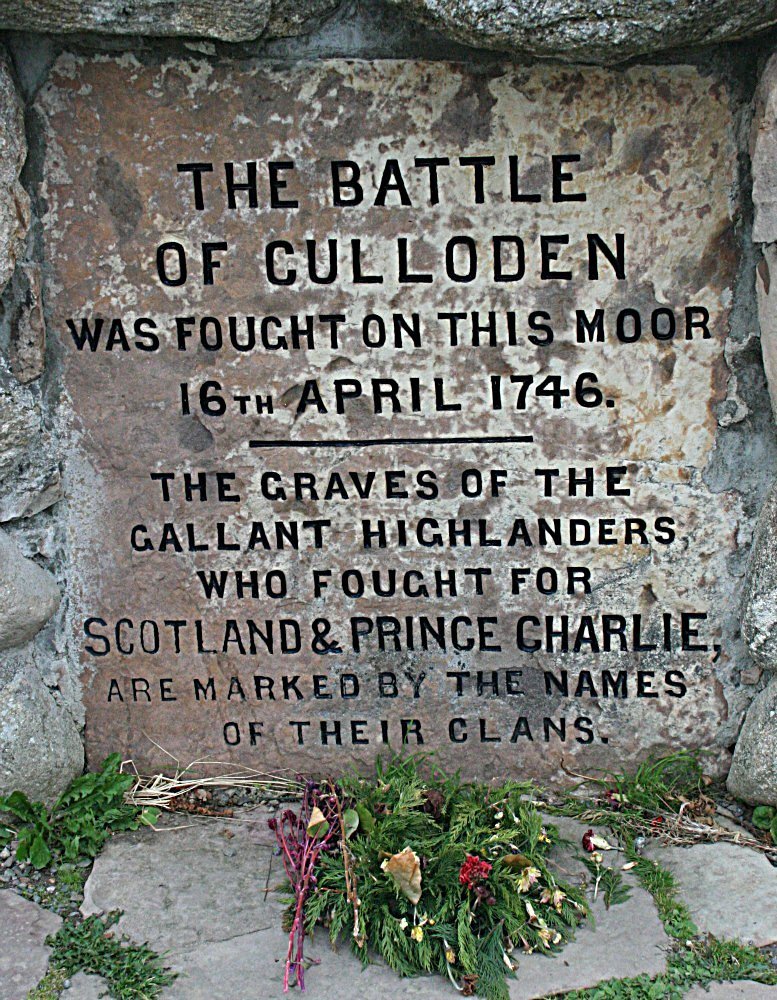

Culloden Battlefield – War Grave

If you know next to nothing about this place at the beginning, you’ll probably be brought up short when you see the site is actually a war grave and not just an afternoon’s diversion.

The visitor centre has a wealth of information panels, audio texts, artefacts, and sound tableaux. It means you can get your head round the significance of this historic site and understand its place in Scotland’s story.

Perhaps the element that will leave the strongest impression is the audio-visual that plays on all four walls of a dedicated room. It evokes Culloden battlefield in all its slashing, smoky, blood-soaked grimness.

Then there are more artefacts, plus material recovered from the battlefield and a very illuminating kind of large table on which the battle is played out diagrammatically, almost like a computer game. (The NTS describe it as an ‘animated battle table’.)

Incidentally, In such an atmospheric place, it’s not surprising that there are several ghost stories about Culloden. (That link takes you to some more Scottish spooks.)

Last time I was there, (anonymously, as is our preference), by a happy coincidence, the Redcoat (aka NTS guide) giving the talk picked me out to help demonstrate how to handle a musket if you were a nervous soldier.

That was fun. It’s all very illuminating. Obviously, the gun wasn’t loaded but gave a pleasing ‘click’!

There’s plenty more on Culloden Battlefield below. But take a look at some of the other reasons to visit Inverness, right here…

The Culloden Battlefield Visit

The real site of the battle lies out beyond the visitor centre – windswept sometimes, even bleak, but pretty atmospheric.

If you do the inside part of the visit first – artefacts, information panels, presentation, plus impressive battle audio-visual – one of the vivid impressions from the way the battle-site events are portrayed is a sense indecision and hesitation.

The Jacobite officers under Prince Charles, were uncertain and in a state of disagreement.

Maybe they knew it was all going to go wrong for them…or maybe it was sleep deprivation after a night march.

When they finally ordered the often unstoppable Highland charge, it was ragged and uneven, with only the right wing making impact.

Outgunned and out-manoeuvred, it was all over for the Jacobites pretty quickly. (There’s more detail the clansmen’s fighting technique fought further down the page.)

The Brutal Aftermath Of the Battle

The visitor centre displays make much of the brutal aftermath, after Bonnie Prince Charlie had been led off the field. The wounded were bayoneted where they lay.

Even locals who had wondered out from Inverness for the entertainment were butchered on the road by government forces (ie the ‘British’ army), who had been instructed to spare no-one in their hunt for the Prince.

No British Army regiment today lists Culloden in its Battle Honours.

But even in the midst of carnage and reprisal, there was obviously time for a bit of souvenir hunting.

A government volunteer afterwards wrote that after the battle ‘Inverness became a wonderful exchange for an odd variety of Merchandize.’

Talking of which, there is a very good shop in the visitor centre (and a café). And such artefacts in the main displays!

Just a few examples: a ticket to see the trial of Lord Lovat, a Jacobite leader, in London. (He was executed.) A letter in French from Bonnie Prince Charlie himself to King Louis of France, asking for more money.

And a load of other interesting stuff. Browsing here is just the way to spend a wet afternoon. (Actually, it doesn’t even have to be wet.)

Culloden – A Scotland Must See

I remember the ‘original’ visitor centre as quite an emotional place. The NTS have avoided sentimentality of the ‘Wae’s Me for Prince Chairlie’ sort with this impressive offering.

Instead, they offer a fascinating analysis of the significance of the last battle fought on Scottish soil. It’s a Scotland ‘must see’.

The tartans worn at the battle by both sides, many historians point out, could not be used to distinguish friend from foe in the field. Instead that was done by badges – hence the famous ‘white cockade’ of the Jacobites.

So, did the National Trust for Scotland get it just right with the interpretation and the visitor experience at Culloden? Yes.

Can the same be said for their even newer visitor centre that deals with the Battle of Bannockburn? Follow that link for our thoughts on that one.

As you will probably visit Culloden if you visit Inverness – best take a look at our dedicated 48 hours in Inverness page.

And down at the other end (the Fort William end) of the Great Glen there’s a super walk to the High Bridge that also played its part in the story of the Jacobites and Prince Charles Edward Stuart. More to read on how the Highlanders fought, just below.

Some myths about Culloden.

Well-respected Scottish academic and historian Murray Pittock is the author of several works dealing with Jacobitism and the Battle of Culloden itself, including ‘Culloden: Great Battles’. It’s well worth reading for its correction of some of the misconceptions in our interpretations of this pivotal event.

In a piece for History Extra (the website for the BBC History Magazine) Pittock also draws to our attention to these myths that grew around the battle.

For example, he points out that Culloden wasn’t at its core a Catholic versus Protestant confrontation but that, in fact, many Jacobites were motivated by opposition to the Act of Union (with England) in 1707. Jacobite recruiting strategy reflected this.

Then again, it would be inaccurate to see the conflict as one between old-fashioned clans and modern artillery – when in reality the Jacobite army was pretty well equipped, and its soldiers certainly not solely discontented Highlanders.

In short, it is easy to over-simplify the motivations and the political or religious backgrounds of the participants.

And it seems even the battle site itself, often described as poorly-chosen ground, can be seen as a logical choice: a level, open place close to the Jacobite HQ at Culloden House. From there, the road to Inverness could be defended.

Battle Tactics of the Clansmen

– Dealing With The Highland Charge

Here is a slightly bloodthirsty memory from my own schooldays. (Indulge me here, will ya?)

I remember at school my history teacher, chalky gown flowing like a Highland plaid, demonstrating General Cumberland’s plan for his regular soldiers to deal with the previously unstoppable Highland charge.

I want you to imagine this. You are a government soldier on Culloden battlefield…

In plain sight on the bleak moor, there is a line of hairy, dishevelled, sleep-deprived and ferocious Highlanders yelling and screaming as they ran towards you. Swords are upraised in their right hands; targes (round leather shields) are held out in front with the left arm.

You fire your musket, helping make a few gaps perhaps, but haven’t time to re-load so you are going to hold the bayonet out in front, instinctively, while thinking that maybe the navy would have been a better career choice after all…

Grim looking Highlanders, swords at the ready

Wait, what about those grim-looking Highlanders, swords upraised, roaring towards you?

Don’t worry, it’s going to be OK, because General Cumberland had seen Highlanders in action before – probably the 42nd Regiment of Foot at the Battle of Fontenoy (in Belgium).

Then they were on the brave but losing Hanoverian side against the French. But Cumberland could see the Highlanders’ preferred tactics.

In a close quarter encounter, they took the bayonet thrust on their targe, turned it aside – which exposed the soldier’s body – then cut down with their sword.

It all happened in a swift movement: engage bayonet with shield on left arm, turn blade aside, then cut down with sword in right hand.

The result was spectacularly messy.

Think about it. Better still, try it out in slow motion with a partner or friend. (Or do it quicker if it’s someone you don’t like.)

General Cumberland’s solution to the clansman’s sword

The story goes that Cumberland instructed his men not to thrust the bayonet at the Highlander in front but to the Highlander immediately to their right – in effect, underneath the upraised sword arm.

If you think about it, raising the sword arm has exposed the Highlander’s chest.

This naturally assumes that the soldier immediately to your left simultaneously deals with the Highlander directly in front of you. Because this opposing wild clansman is intent upon opening you up like a haggis on Burns Night.

Yes, the history class that day was a great success and we must have practised for hours in the playground afterwards.

And I recalled that, as a cheeky young pupil, I pointed out to the teacher that the tactic would not have worked against left-handed Highlanders and that it assumed that the two lines met at the same moment.

But, looking back, wasn’t I lucky to get real Scottish history at school?

The suggested itinerary for two days in Inverness includes a visit to Culloden Battlefield.